It's been a while. More than a whole year! But this is what we've been working on while we were gone. Please visit www.empireoffunk.com for more information! We have some crazy events coming up! Come meet the authors and artists of Empire of Funk!

Sunday, May 4, 2014

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

Brown Mass Hysteria: Filipino Americans patronized by a diverse audience

|

| Bambu rocking a sold-out The Echo in Los Angeles on Friday. The crowd was probably predominantly Chicano/Latino and Filipino. (Photo by Joseph Alvaro) |

|

| Filipino/Mexicano emcee Odessa Kane representing "Cuetes and Balisangs" for Southeast San Diego. (Photo by Joseph Alvaro) |

In the United States, Filipino American hip hop artists have had better results in finding a captive public in hip hop compared to their counterparts in the Philippines. Many (not all) Filipino American hip hop artists, especially on the West Coast, know very well that many Filipino Americans will support them at shows, patronize their music, and buy their merchandise.

But, what happens when Filipino American artists' audience move beyond a predominantly Filipino American audience? On Friday night, a whole posse of Filipino American male emcees (Double Dosage, Kixxie Siete, Odessa Kane, and Bambu) rocked a sold-out crowd at The Echo in Los Angeles. Sure, there was the usual Filipino American fans, but I would be confident in saying that the house was loaded with young Chicanos and Latinos who may have outnumbered the Pinoys. And just like the Pinoys, these folks were mouthing the lyrics of the performers on stage and pumping their fists just as high.

Kixxie's Hawthorne/South Bay fanbase, Odessa Kane's Filipino/Mexicano-centered lyrics, and Bambu's Soul Assassins affiliation (the crew of Cypress Hill) can certainly attribute to the very distinctly Los Angeles hip hop demographic. At one point, Bambu yelled out: "We were all colonized by the same people anyway!"

|

| Bambu performs for the last time with the new daddy-o DJ Phatrick. (Photo by DJ Phatrick) |

And, for some reason (even though I am not surprised), I am curious as to the meanings of non-Filipinos who are drawn towards/indulge in/recite/embrace Filipino American-accentuated music and culture. What happens when Filipinos have a non-Filipino audience? Are they attuned to the Filipino-related lyrics? Do they identify with Filipinos? Do they hang out with Filipinos? If not, how are Filipinos relevant in their lives? Where do Filipinos appear in their imagination within a field of racial and ethnic power? How are Filipinos made legible to the non-Filipino cultural imagination aside from this music?

For the Asian Americans (non-Filipino) in the crowd: How do Asian Americans identify with Filipino Americans? If Filipino American hip hop artists have become (or have always been) dominant in music relative to other Asian American groups, what kind of identity-labor is done to align with Filipino issues? If Filipinos are marginalized culturally, politically, and academically (except for recent anti-imperial scholarship) when it comes to the pan-Asian American umbrella, what kind of value do Filipino American hip hop artists retain as cultural/racial "border crossers" who magnetize non-Filipino Asian Americans? Could/should/can Filipinos be embraced for their cultural value, and still be marginalized in other realms of Asian American power?

Or maybe that's it: Filipino American artists have a certain draw (power) because they are so flexible. They can somehow touch the souls of people of many backgrounds.

And that seems to be the ongoing trope: Filipinos somehow appear nowhere and yet appear for everyone at once. A Filipino is invisible in the larger schema of our cultural imagination, yet she/he is also right there all along.

Like famous Manila tour guide/activist/performer Carlos Celdran says: "Filipinos have little unique about them. And that's precisely what makes them so unique!"

Being unique yet broadly resonant seems to be a formula working for the fast-growing scene of Filipino American artists in hip hop.

---

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Hip hop on the mainstage in the Philippines!

It's almost here! Looked down upon for so long, Philippine hip hop finally has a mainstream, "legit" stage to showcase its talent at the Araneta stadium. The acts are excited to take Pinoy hip hop to the next level. Bubbling just beneath the attention of the public and given a valiant push in recent years by homegrown artists, will Pinoy hip hop finally erupt and become embraced by the masa? Will Original Pinoy Music put hip hop center stage?

Lezgoo!!

---

Monday, November 12, 2012

Not Giving In: Beautiful slum x bboy uplift

Hello again world! I've been doing other projects lately, but I just had to post this beautifully done Philippine bboy uplift and escape narrative featuring the music of Rudimental. The shots are artfully done, and it seems they have a balloon or a helicopter camera. The acting is superb.

The neorealistic video tells the story of Ereson Catipon aka Mouse a bboy from the harcore slums who dodged many obstacles to become a Philippine bboy champion. He moved to UK in 1996 and continued to win championships in UK and worldwide.

The guys at Epicenter--the "Sports Center" for Bboys and Bboy culture--had a chance to interview Mouse at the beginning of their 6th episode. You can listen to this interview here, beginning around 10:50-30:20:

Special thanks: Chesca and Chris Woon!

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Tastemakers of the Metro? Philippine hip hop DJs shape hip hop's "soul"

|

| DJ Arbie Won diggin in the crates at his record store |

A flourish of guitar strings, the clap of crisp snares, and the boom of kick drums drive the beat as a vocalist croons a sultry melody. This musical ambiance accompanies the decor of DJ Arbie Won's record shop, which stands as a testament to a particular hip hop sensibility. Iconic hip hop imagery such as Run DMC posters decorate the walls, stacked crates of rare vinyl hug the sides of the room, a photo of an Egyptian pyramid dangles below the air conditioner unit, and a number of turntables and beat machines lay around. A customer "digs" in a crate of soul records.

As we chat, samples of Arbie Won's upcoming album United Freestyles 3 plays in the background. The music can easily pass as "state-side" independent hip hop except for the occasional Tagalog rap performed by local emcees, some veteran and some up-and-coming. Arbie's beats sound smooth and refined, almost like 70s soul with a hip hop snap.

He explains that United Freestyles 3 is the third edition of his famed United Freestyles series, the first which was a rough and rugged "one take" freestyle cipher with thirty emcees. This fabled album, recorded at the height of Philippine hip hop in 1999, was followed by the second edition in 2005, which received the First Annual Philippine Hip Hop Music Award album of the year. (Click here to hear "Taken In" from this album).

In a music-oriented nation with an array of genres, DJ Arbie Won's particular hip hop taste is shared by many Filipino music fans. As seen by the collection of emcees featured in the United Freestyles series and the growing independent hip hop scene in the Philippines, hip hop culture boasts fierce creative circles, where both original Pilipino hip hop and state-side knocks are celebrated.

Groove Blocked

But according to some DJs, this type of music would probably not be heard in typical Metro Manila dance clubs.

"People are close-minded with music here," DJ Thea says. She believes many club promoters misunderstand hip hop, usually dismissing it as "yelling music." This negative attitude towards hip hop by promoters is reflective of the treatment of hip hop on a larger (national) scale.

Thea (aka DJ Teaze), who is credited with being the "first Filipina hip hop DJ," is a resident DJ for the Metro's biggest clubs such as Republiq and Prive and shares some of Arbie Won's musical hip hop preference. Hailing from Baguio, which was founded as an American city and celebrated its centennial in 2009, Thea attended an international school. She would receive state-side hip hop music from her black and white American friends who made frequent trips to the States.

Even though she is a sought-after club DJ, the type of music at clubs she spins for are at odds with her musical upbringing. "Promoters prefer 'open-format' music," she explains as we chat at a cafe. "Open-format" is a generic term used to describe a mash-up of house and popular American radio music. "They want music that's above 128 beats per minute," Thea points out.

Hip hop, as "slower" music, seems to have no home in the Metro's clubbing scene. "Knowledge of hip hop has nothing to do with professional DJing in clubs," she says. Thea, who associates hip hop's sound to a jazz tradition, mentions that in some clubs if there is "too much dancing," then the bouncers will kick you out. I saw this practice for myself at Republiq a few years ago. When party-goers get into a groove and gain attention, the bouncers will intervene.

As a resident DJ of Prince of Jaipur club from 2005-2008, she witnessed the rise of the so-called "era of the superclubs." The infamous Embassy superclub, located next to Jaipur, opened in 2005. "I played hip hop and people had fun. There was no dress code and we had a faithful following of hip hop fans and dancers."

But when Jaipur began to emulate Embassy in 2008 by instilling a dress code and a "superclub feel," the regular Jaipur clientele stopped going. "Some people were blocked because they were wearing 'hip hop clothes,'" Thea remarks. "Dancing for fun stopped."

|

| DJ Thea (aka DJ Teaze) chatting at a cafe |

Despite the seeming twilight of the kind of hip hop Thea and her Jaipur audience enjoy, DJ Jena, Thea's "4X2" turntablism partner, has a more optimistic vision of hip hop's trajectory in the Philippines. The duo, who perform beat juggling on four turntables, has toured in Singapore and Qatar for sold out audiences.

"I'm not exactly against it," Jena says about superclubs' peculiar musical choices. "I like making money. And I love seeing people have a good-ass time. Are superclubs and hip hop in direct opposition? No. Are superclubs and that old golden era of hip hop in direct opposition? Yes. It is what it is."

Sure, the "golden era of hip hop" (which could either mean state-side jams or original Pilipino hip hop that had its hayday and payday in the 1990s for Filipino artists seeking mainstream deals) is a thing of the past, but does that mean Philippine party-goers have abandoned it forever in exchange for "open-format?" As I have written in a prior entry, some hip hop advocates in the Philippines believe right now is the "golden era of hip hop" in the Philippines because of the enormity of creative production happening today.

But, as the DJs will tell you, you won't hear anything "golden" in the club. But that might be ok. "Hip hop music might not sound exactly the same as it did in the past. But it does sound new. I like new," Jena admits.

Playlist Operators?

Certainly, the music has changed since the 1990s, but how much control do DJs have in shaping the reception of new music, especially when much of the music being produced by Philippine artists are not even getting much love by Filipinos? If "open-format" cannot accommodate hip hop (at least at this point), even more does it fail to promote original Pilipino hip hop.

Philippine DJs are in a constant struggle to be a part of this changing musical soundscape, which does not always sound the way they'd like. But they spin anyway. And as fans first, their profession is rooted in a passion for hip hop.

DJ Arbie Won's moniker "The Beat Traveler" serves him well. His musical journey began in 1991 in San Francisco where he used to carry crates for his uncle's mobile DJ business. He moved to Manila a few years later and brought all his records. Because he owned the latest music, he would make mixtapes for artists who were interlocked with the brewing Philippine hip hop scene. Soon enough, he was invited to join the hip hop crew Urban Flow, got signed to a label, and things took off from there.

|

| DJ Jena on deck at B-Side. Photo credit: B-Side |

DJ Jena's journey was similar. Of a younger generation, Jena grew up in the Los Angeles and Seattle where she immersed herself with hip hop. She became a DJ after attending college in Manila. Now she has become a staple in the sonic world of the Metro.

Without a "state-side" background, as mentioned earlier DJ Thea was exposed to hip hop via her American friends in Baguio. After moving to the Metro in 1999 and before becoming a professional DJ, she performed as a "hype" dancer at clubs with a crew of girls, some of who would eventually become members of the world champion Philippine All Stars hip hop dance group. Starting off as a dancer prepped her ears for playing good dance music. Today, she is a member of the Styles Team, a group of DJs and emcees (or more accurately hype men) hired to rock parties across the Metro.

Arbie Won, who also spins at big clubs, sometimes sneaks in two or three hip hop songs, a risky move he thinks few DJs attempt because of the unsure reaction of the crowd and the promoters. Thea plays this subversive game as well, often playing tried and true hip hop anthems at the end of the night (think Arrested Development, SWV, Tribe Called Quest, Naughty By Nature, etc.) when the crowd is thinner, the people are drunk, and a few hip hop fans stick around.

Their professional expertise as musical performers is called into question in the era of superclubs. According to Thea, DJs are often treated as employees--not as creative performers--who are paid to play what people want, like someone who operates a playlist from an iPod.

|

| Arbie, Thea, and Jena spin at Boom Bap Friday at B-Side, where hip hop is loved and promoted in The Metro |

Arbie Won has a more hopeful outlook at the state of hip hop at clubs. Aside from the occasional "sneaking in" of hip hop in the bigger clubs, he plays hip hop at smaller venues, such as Alfonso's in Ortigas or at the Distillery in Makati, that cater to a niche audience. "I can play hip hop not for a big crowd like at superclubs, but for sixty people who allow you to take them on a journey."

Will a Philippine party crowd in 2012 allow a hip hop DJ to be the captain of their party?

In a country that for the most part tends to disparage hip hop, the hip hop DJ continues to confront an uphill challenge. Arbie laments, “It's sad because Philippines should be leading in hip hop. Other countries support their artists. It’s not about money so much as ignorance of record industry and promoters.”

The Philippine Difference

Regardless of an unreceptive clubbing audience, Philippine DJs and artists are spinning and creating hip hop in their own ways, and with small but passionate hip hop circles there's no sign of it slowing down.

Given the more frequent appearances of Philippine hip hop artists on daytime shows and in marketing campaigns, it may not be a question of if hip hop will become embraced by the mainstream Philippine populace, but how mainstream Philippine hip hop will sound/look like. Will it be "indigenized" and sound more "foreign" than the American-style of hip hop cherished by many hip hop enthusiasts? Or will it sound like the hip hop of Arbie Won's United Freestyles series? Or will it be a balance of both sensibilities?

Whatever the case, the Filipino/a hip hop DJ plays a key role in popularizing and celebrating the rise of Philippine hip hop. On the crowded dance floor, the DJ has a special opportunity to be the captain, and accompany Philippine hip hop on its journey.

Special thanks: Thea, Arbie, Jena, Chesca, Justin Breathes, Jerome Smooth, Leo, Teishan, and Vince.

---

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Gunshot Sounds of Seattle: Prometheus Brown's "May Day"

Asked to write a Seattle Times guest column in response to last month's deadly shooting spree in Seattle's University District, Blue Scholar's Prometheus Brown wrote a song instead. He wrote "May Day" to address the less-acknowledged and more pervasive violence in the city. (Lyrics and media below)

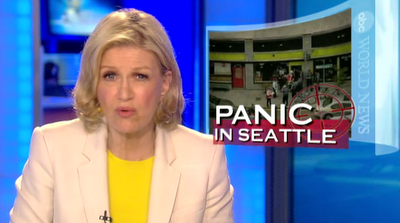

A media spectacle erupted around the May shootings in a city that, according to a ABC news clip, "prides itself as one of the safest big cities in America."

Stirring a firestorm of internet controversy, Pro Brown's "May Day" attempts to debunk the myth of Seattle's"safe" reputation. Do we really know whats going on in "grimier environments," where shootings and other acts of violence happen frequently?

|

| Aftermath of the May shooting spree |

Pro Brown's song is dense with layers of references and images (Spike Lee's provocative 1989 movie "Do the Right Thing" reveals Brown's generational sensibilities), but is clear in its indictment of popular media's tendency to sensationalize violence in so-called "safe" urban areas, when violence in the hood is often left ignored. It seems there exists a double standard: some lives are worth more than others.

Pro Brown doesn't valorize the hood or champion its condition. Instead, "May Day" laments the situation that folks have no choice but to live in and criticizes the expectations made by city officials and commentators that marginalized people must "act right" as "proper citizens" in order to be fully enfranchised. Brown says, "They saying that you gotta act right if you wanna have rights, but what if you were born into a wrong situation?"

Sadly, violence has become normalized in certain parts of town. "It’s something that’s been happening for a long time in the south end." Certainly bounded within the geography of Seattle's metropolis, the song illustrates that the south end is not fully enfranchised. Sure, there is "panic" in Seattle, but there is also an indifference to people's lives in abject areas. Perhaps the disavowal of the conditions of the latter is necessary in creating the mythology and materiality of a "safe" Seattle.

Prometheus also alludes to the danger impacting Philippine journalists who for some time have been "disappeared" due to their investigations of the Philippine military and government. He urges us to see the links between the dangers confronted by ordinary citizens in the lesser-respected parts of town and that of Philippine journalists who testify to injustices. Both bear witness, and both are vulnerable to death due to state-complied violence.

What happens when our collective consciousness normalizes violence, especially when it is targeted toward groups that are stripped of voice?

How long does it take for our collective consciousness to "wake up" from the numbness, indifference, or ignorance we have towards the chronic premature death of black and brown people? How many more Trayvon Martins or South Side Chicago shootings?

Prometheus does not claim to have the answers, but he says "neither does a person who practices double standards."

"May Day" is concise, smart, subversive, and should prompt us to rethink what is being normalized and provoke us to change those grievous conditions.

Never heard of this, city getting murderous —

occupation dangerous like Philippine journalists.

Crazy and deranged they describe him in the same pages

that would call him terrorist, if not for the melanin deficiency.

Gang problem bigger than just juvenile delinquency.

Gangs is survival if environments is grimy.

To begin with — speaking of which, let’s be consistent —

Today is called a tragedy, yesterday a statistic.

I’m listening, before I ever speak upon insisting.

My name is young Prometheus and this is my opinion:

Watch “The Interrupters,” see ordinary civilians

can police themselves before they have to call police for help.

At least a little space to breathe, if you believe all violence

is abhorrent to your being, then why you oversee it?

If the killer wears a uniform but if the killer’s me,

it’s normal if the victim also looks like me.

Shots fired in the south end, nobody cares.

Shots fired in the north end, everybody scared.

Nothing they can do for us that we can’t do ourselves.

Point the finger at the mirror instead of somebody else.

Shots fired in the parking lot, nobody cares.

Shots fired in the coffee shop, everybody scared.

Nothing they can do for us that we can’t do ourselves.

Point the finger at the mirror instead of somebody else.

Can’t lie, I know the music can be influential,

but not as influential as desperation. They saying

that you gotta act right if you wanna have rights,

but what if you were born into a wrong situation?

Moral relativity — that passive aggressive city stuff —

becoming history quicker than you can blink at me.

Rule 1: Protect yourself at all times.

Rule 2: Always end but never start a fight.

Came up in the era of the hand-to-hand scrapping

‘til the drugs happened, now it’s bloodshed at transactions.

I’m calling time out like Samuel L. Jackson

playing DJ Love Daddy with the African medallion.

Tryin’a do the right thing. I don’t have the answers,

but neither does a person who practices double standards.

If every death’s a tragedy then join us when we’re chanting,

and not just when we’re singing and dancing. Too many

shots fired in the south end, nobody cares.

Shots fired in the north end, everybody scared.

Nothing they can do for us that we can’t do ourselves.

Point the finger at the mirror instead of somebody else.

Shots fired in the parking lot, nobody cares.

Shots fired in the coffee shop, everybody scared.

Nothing they can do for us that we can’t do ourselves.

Point the finger at the mirror instead of somebody else.

Prometheus Brown, also known as George Quibuyen, lives in the Rainier Beach neighborhood of Seattle.

---

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

FlipTop flowin the dough in: The sponsorship era?

Si Kuya Guard knows wussup.

Our FlipTop favorites Batas, Loonie, and Abra are at it again, this time in a heated battle with the legendary Pinoy rock group Parokyo Ni Edgar. Everyone knows its bout to be on, especially Mr. Guard in the back nodding his head (ha!).

This TM Tambayan ad is nicely shot and pretty satirical. FlipTop and its stars are now gaining sponsorship. In the ad, these rap acts are visually parallel to the more widely-accepted, "safe," and recognizable rock group Parokyo Ni Edgar. The money is beginning to flow for the once underdog, underground, little-known FlipTop hip hop scene. Will it only get bigger?

---

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)